Consider The Cowpath

I recently gave a mini PechaKucha-style talk at SVA IxD about habits and cowpaths and such, which I’ve reproduced here:

One day, when I was about thirteen years old, I decided to bike from my house to Brooklyn Heights for the first time. All was going fine… until I nearly merged onto the highway. (Don’t worry. I veered off, found a payphone, and called my mom for directions. She almost had a heart attack.) Why did I almost make such a boneheaded decision? Well, I was following the route my mom used when she drove us to school every day. She took the Prospect Expressway, so I was going to do the same. It was the path I knew the best, and habit is an extremely powerful force — one that problem-solvers ignore at their own peril.

In the IT world, we like to blow up bad habits. We have a phrase for this: “don’t pave the cowpath.” In other words, wouldn’t it be nice to come up with an objectively superior solution for a problem, rather than cementing the jury-rigged method that some former employee implemented some Friday afternoon ten years ago? This sounds really good, but it’s shortsighted. If we try to torpedo an existing system, human nature — those bad habits — will still find a way.

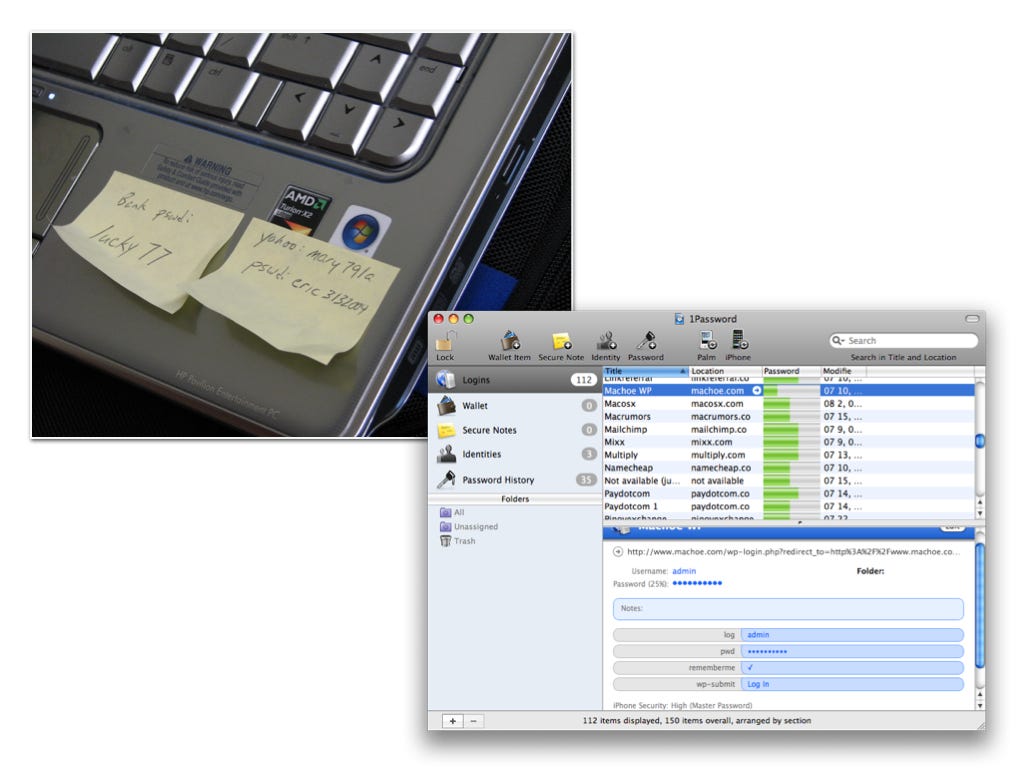

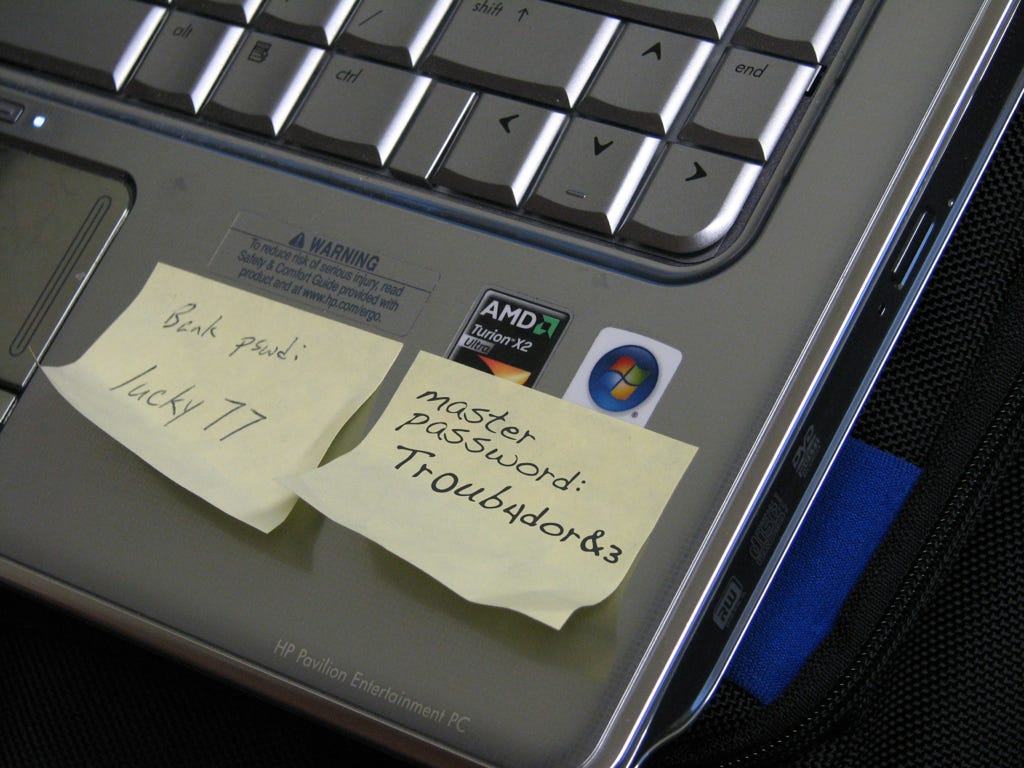

Take, for example, the mysterious case of the client who likes to keep their password on a Post-It stuck to their computer. As an IT consultant, I come in and my eyes bug out. I say, here, let me set you up with a fancy password manager. It’ll solve all your problems, it’s really pretty, and all we have to do is set up a master password so you can use it. So what happens next? (img)

Of course. My client has simply scrawled their master password onto the Post-It note. Why? Well, zooming out, maybe we weren’t solving the right problem. Their goal was to remember their password and easily access their files. Perhaps instead of undoing the Post-It cowpath and introducing a much larger security breach, we can dig deeper and solve the unspoken problem. So, what is the problem?

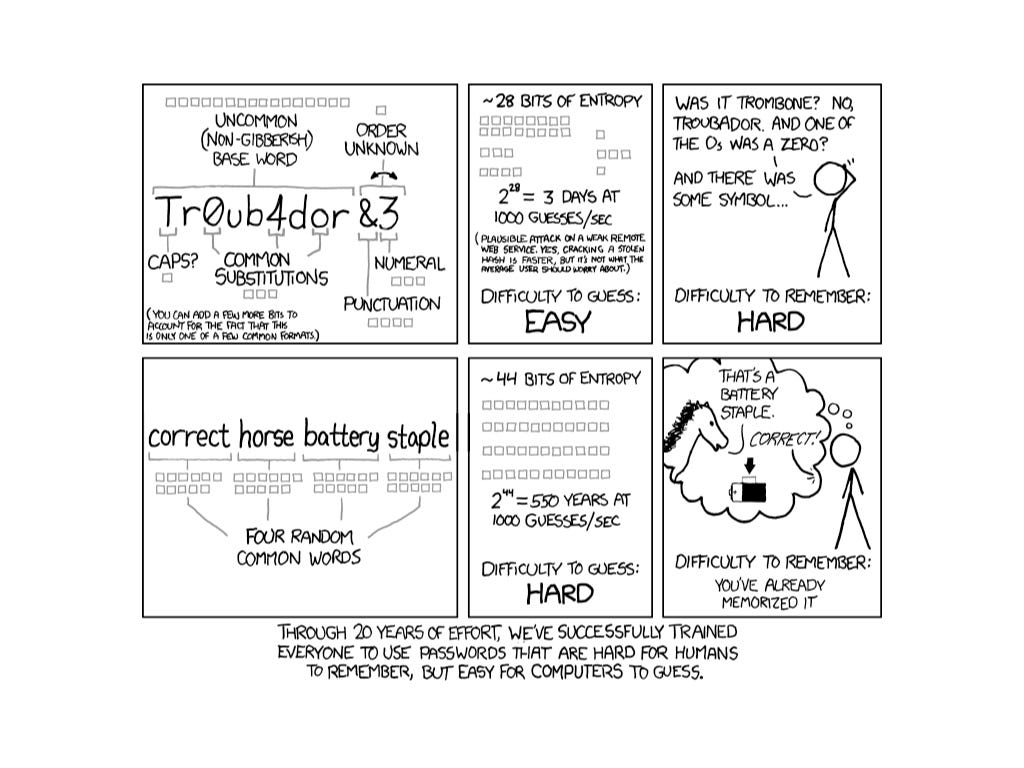

As usual, XKCD has the answer. It turns out, apparently, that we’ve all been crafting terrible passwords for years. Adding complex numbers and symbols is (relatively) easy for a computer to brute-force, but nearly impossible for a human to remember. Choosing a random string of words, like “correct horse battery staple,” is far easier for a human to commit to memory, but far harder to crack. By looking at the root of this issue — convenience and ease of memorization — we’re far more likely to keep the password off the Post-It.

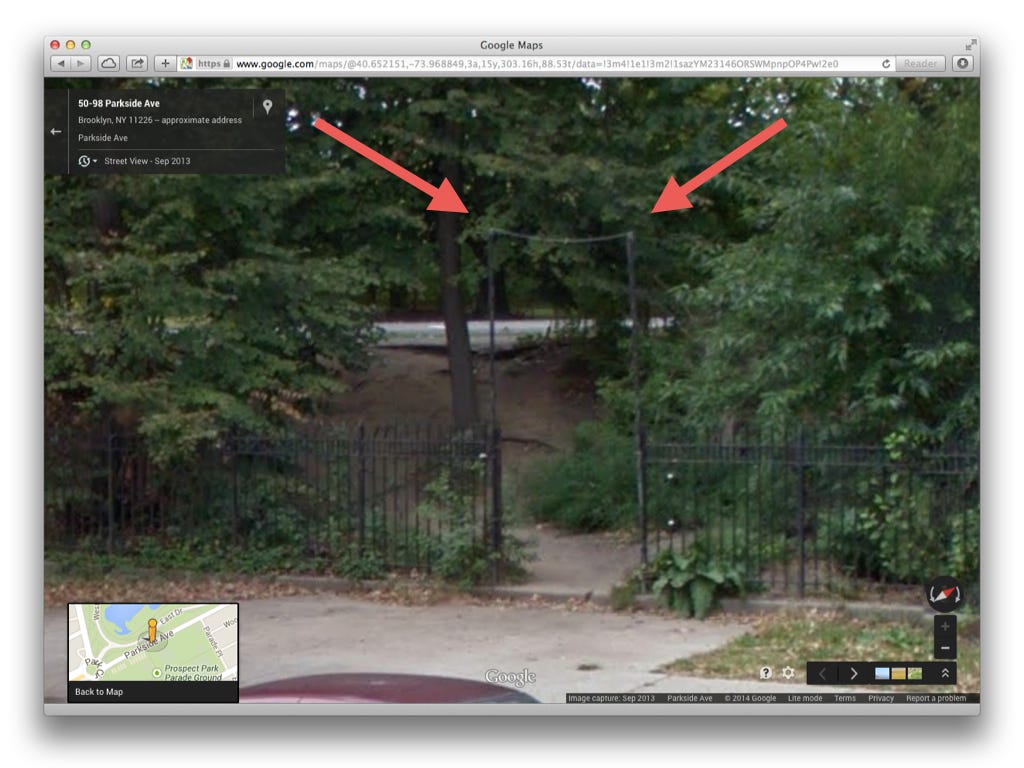

Getting to the root of the problem involves noticing that some seemingly-senseless paths are intentional — these are known as desire paths. Returning to the parable of my fateful bike ride, it turns out that the best way to get to Brooklyn Heights from my old house is to cut across the Parade Grounds, dart across a long street with heavy, near-continuous vehicular traffic, and walk your bike through a hole in the fence around Prospect Park. No matter how many times the Parks Department puts up a new fence, folks keep tearing it down, because the alternative (biking around half the park to get to the proper entrance) is so onerous. Rather than try to rebuild the fence and correct the behavior, perhaps we can embrace it — by putting up a traffic light, for instance.

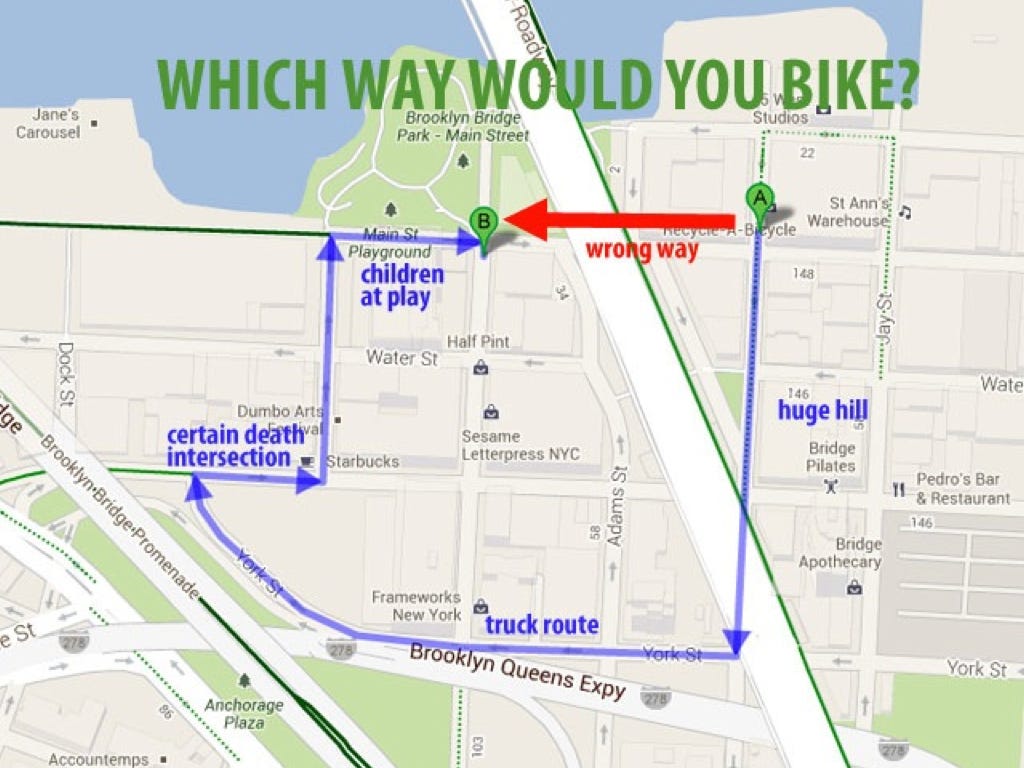

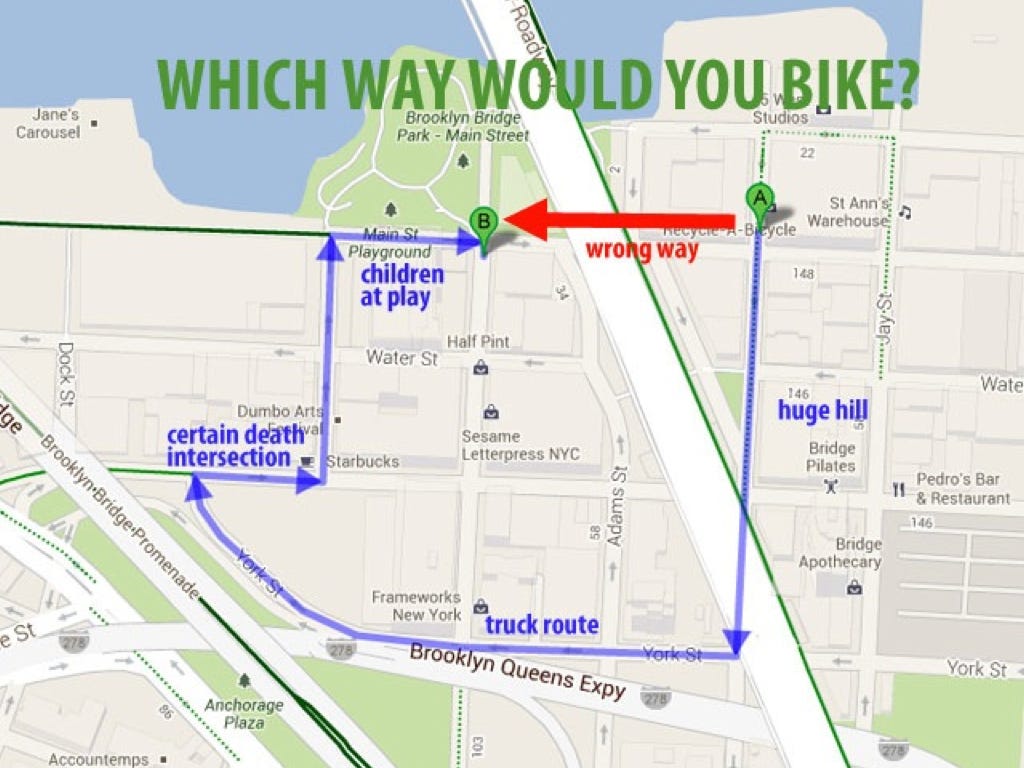

Similarly, by paying attention to what’s going on and trying to withhold judgment, we might (might!) learn that a cyclist biking down a one-way street against traffic is actually not an asshole. Perhaps he’s not even going the wrong way. Maybe he’s made a prudent decision that this route is the safest and most expedient, and maybe instead of giving him a ticket we can design a solution, like a protected two-way bike lane, that would be m

ore effective. (img)

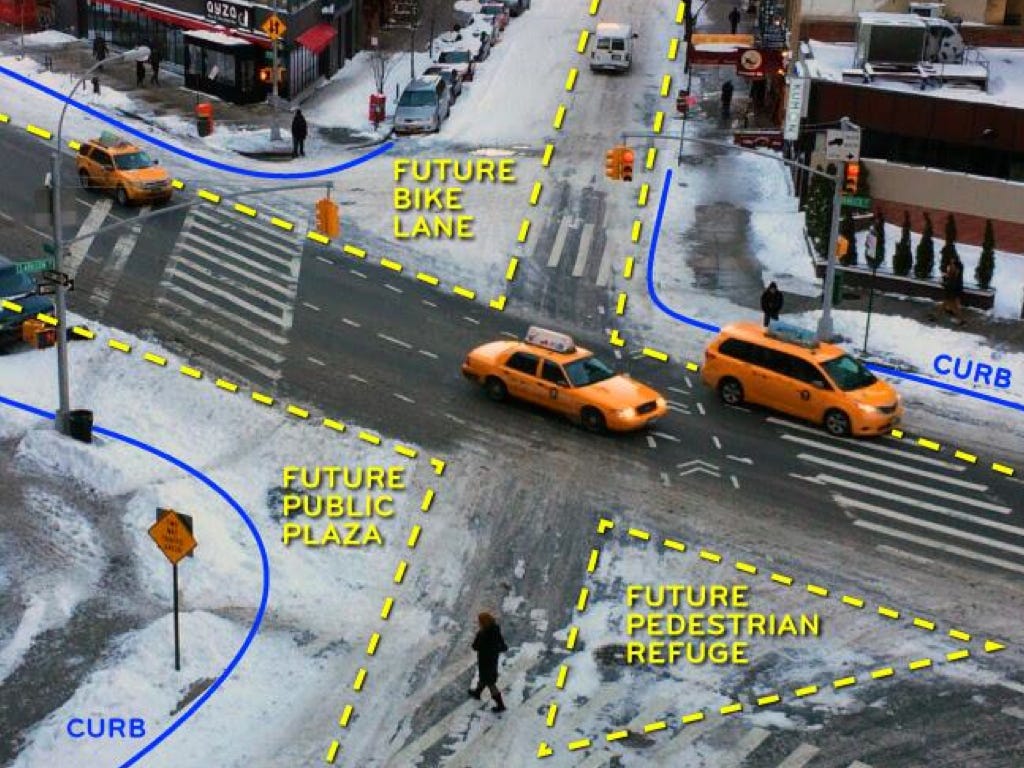

Sometimes the behavior we must design for is largely invisible, so we have to get creative. Here, looking at the tracks that cars leave after a snowstorm, we can see the desire path developing in negative space. The cars have done the research for us, and now we can identify an obvious spot for a pedestrian refuge. This behavior isn’t accidental, but it does require a well-trained eye to observe it. (img)

And for another example of nearly-invisible behavior, here’s a closeup of that desire path into Prospect Park. Take note of that string bridging the gap in the fence. That’s part of an eruv, which is a consecrated, unbroken filament strung around entire neighborhoods to virtually extend the borders of Orthodox Jews’ households on the sabbath. Designing for this space requires awareness of many diverse, hidden needs — none of which we can ignore, and all of which will route around any obstructions.

The moral of the story is that life finds a way. Habits are powerful, and behavior is stubborn. It also usually has an internal logic, even if that’s sometimes hidden on the surface. In order to design mindfully, we have to embrace these “bad habits” and figure out their root cause, rather than torpedoing an existing system in favor of an impossible “objectively superior” solution.